|

On Dec.

16, 1773, the first permanent Jewish settler in Baltimore, a Sephardi named Benjamin Levy, took out a full-page ad in

the Baltimore Advertiser promoting the merchandise in his wholesale and

retail store on Market Street at the corner

of Calvert. On Dec.

16, 1773, the first permanent Jewish settler in Baltimore, a Sephardi named Benjamin Levy, took out a full-page ad in

the Baltimore Advertiser promoting the merchandise in his wholesale and

retail store on Market Street at the corner

of Calvert.

There, “for ready money,” one could buy “… a large assortment of Corks for

bottles … rubber for tables, tea, coffee, chocolate, buckets, pails … fine

pickled Salmon, Irish beef, rose blankets, English cloth, rugs, felt hats,

silk and cloth umbrellas and sundry other articles.”

Levy’s establishment was a precursor of the palatial department stores that

immigrant Ashkenazim, largely from Bavaria, would open

a century later.

These stores and their merchant princes are being featured in an exhibit at

The Jewish Museum in Baltimore titled

“Enterprising Emporiums: The Jewish Department Stores of Downtown Baltimore.”

Also featured on a weekend excursion here is “The Cone Collection” at the

Baltimore Museum of Art, one of the world’s major collections of modern art

donated to the museum by the city’s philanthropic Cone sisters.

Now, down the New Jersey Turnpike, across the Delaware Bridge and south on

U.S. 95 directly to our hotel, the Hyatt Regency, overlooking the spectacular

Inner Harbor, the very heart of Baltimore — hometown of the Cone Sisters,

Gertrude Stein, Henrietta Szold and Babe Ruth.

And the new settlers who barely eked out a living as storekeepers. They

mostly had little education, either general or Jewish. Theirs was a tradition

of hard work, thrift and discipline. These storekeepers would keep open their

modest shops from dawn to late night, and would travel from village to

village peddling their wares.

Beginning in the 1830s, substantial numbers of Jewish immigrants from

German-speaking areas of Europe settled in East

Baltimore on such tenement streets as Lloyd, site of The Jewish

Museum. Many brought with them an Old World experience

in buying, selling, trading and bartering.

It was from such beginnings that the merchant class of German Jewish

immigrants would develop. The great department stores they would create a

century after Levy’s buckets, blankets and beef were virtual fairylands for

shoppers. As the museum exhibit shows, the emporiums would feature under a

single roof an endless variety of merchandise, artful displays, enticing

eateries and a stream of special events, entertainments and celebrations.

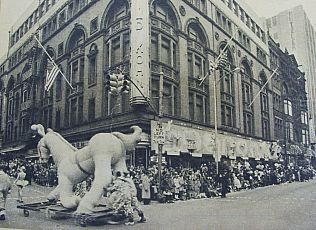

The excitement of the full-blown department store hit Baltimore in 1886

when immigrant Joel Gutman opened his four-story,

30,000-square-foot emporium. The “artistic event of the season,” as it was

advertised, attracted thousands of Baltimoreans who waited in a line three

blocks long to enter the impressive building.

Gutman’s success was followed by other stores of

the same grand stature — Hutzler’s, Hochschild Kohn’s and Hecht’s. The stories of these

institutions illustrate the richness of the downtown experience at its peaks

and the ways in which these Jewish businesses changed Baltimore forever.

Window dressing was the art form created by the stores. Their windows became

cultural showcases providing a canvas on which to depict historical events,

express points of view, honor local achievements and celebrate community

moments, not to mention their primary functions — to sell goods. By

selecting, buying, selling and displaying stylish merchandise, the department

stores became the educators and tastemakers in the complex world of American

fashion.

For many second-generation German Jews with growing purchasing power, the

department stores sold the clothing that would help form their American

identity. The imaginative displays of party dresses, storefronts, high-button

shoes, corsets and flowered hats show what a small museum with limited staff

and budget can do to evoke the entire history of a community.

With the postwar flight of a new generation of Jews from the inner city to Baltimore’s green

outer reaches, the great stores that had shaped their parents and

grandparents fell into decline. Eventually the stores, which had made the

intersection of Howard and Lexington the lively

center of the city’s commercial life, would give way to the shopping malls.

The city’s close-knit Jewish community of 90,000 is concentrated now in

northwest Baltimore and the

adjoining suburbs. A Jewish presence is visible there, mainly on or near

Reisterstown Avenue — as many as 50 synagogues, religious schools, Baltimore

Hebrew University, mikvehs, kosher restaurants,

butchers, bakeries, Judaica shops, a major weekly

newspaper, a wide range of social and cultural activities.

But our main destination this weekend is the museum at the corner of Lloyd

and Lombard, where the Jewish community had its beginnings and to which its

members return on nostalgia trips to recall their own history, housed in

Maryland’s oldest synagogue, dedicated in 1845; to worship next door at B’nai Israel, built in 1876, the oldest synagogue in

continuous use; to eat Jewish-style food in one of the two surviving delis,

around the corner on Lombard Street; and to meditate at the monumental

Holocaust memorial, a short walk from the Inner Harbor.

Also downtown is the Baltimore Art Museum, a world-class institution, and the

J.M.W. Turner show, whose permanent exhibit is based on the Cone Sisters

Collection of modern art.

For a period of 50 years dating from the end of the 19th century, Claribel and Etta Cone, heirs to a great German Jewish

fortune and friends of Gertrude and Leo Stein, their advisers, traveled to

Europe, frequented Paris salons, met Matisse and Picasso among other

struggling young artists, and wisely bought their works by the thousands.

The collection contains 500 works by Matisse, 100 by Picasso and numerous Courbets, Degas, Renoirs, Pissarros

and other icons of 19th and 20th century art. Resisting the friendly

persuasions of Alfred Barr, late head of MoMA,

Etta, last of the sisters to survive, bequeathed the entire collection to her

hometown museum, where it now occupies an entire wing.

|